The Man Called I-L-L-Y-A

The Man Called I-L-L-Y-ANew York Times Magazine

October 24, 1965

The Man Called I-L-L-Y-A

The Man Called I-L-L-Y-A

By Bernard Wolfe

Ten or twelve hours a day, five days a week, David McCallum scales canvas parapets, blasts open paper mache dungeons and pseudo-severs unsavory vertebrae on an MGM

Sound state in Culver City. But on the sixth day he does not invariably rest from his gymnastic labors

Saturday may see McCallum jetting to some American city to be howled at and grabbed for by 300,000, 400,000 or 500,000 rhapsodists who rate him Hollywood’s foremost parapet-hopper, dungeon-pulverizer, vertibra-smasher. On Saturday he had been known to vault nonfictional walls to escape injury to his own nonfictional bones.

McCallum’s fans, sometimes a swarm, often a raging mob, recognize him first

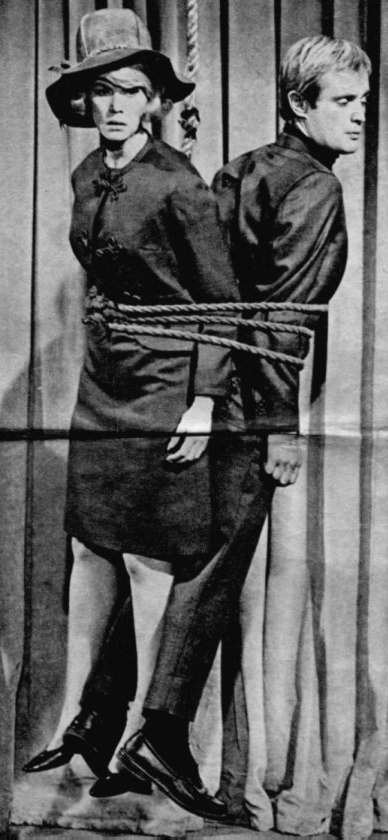

by the black turtleneck sweater hugging his economy-size frame like a nubby

skin. This garment is his trademark on the "spy-spoofer" television

show called "The Man From U.N.C.L.E." McCallum plays the peripatetic

and all but double- jointed Russian law enforcer named Illya Kuryakin opposite

Robert Vaughn’s dapper, hypercool American, Napoleon Solo.

Napoleon Solo.

U.N.C.L.E., to the extent that it pretends to be anything, is a shadowy international policing agency bearing down on blurry malfeasants in the interest of an ephemeral international legality. It’s full name is United Network Command For Law and Enforcement, with the enforcement featured more prominently than the law.

Both the Enforcement and the Law are afterthoughts. In the beginning U.N.C.L.E., while meant to have a certain dilute constabulary function, was nothing so definite as a variant of Interpol. The "premise" of the "format" to use television’s technical terms, was simply that human endeavors fall into two basic categories, the licit and the illicit, and that it might be fun to have the most skilled devotees of the first in weekly hot pursuit of the mot ingenious exponents of the second.

So U.N.C.L.E. was born, an organization with vast laboratories and nerve centers hidden behind a Manhattan tailor shop and global operatives who keep in touch via cigarette-lighter radios and conduct shootouts with wondrous all-purpose grease guns. The best-covered aspect of their undercover activities concerns precisely what laws they are so bloodily enforcing. The most evasive thing about the law evaders pitted against them is the precise nature and intent of their transgressions. To judge from the scant information haphazardly sprinkled through the scripts, these can range anywhere from gratuitous kidnappings to an equally gratuitous infestation-by-missile of the Soviet wheat crops. Spy-like adventuring is desired with no cramping political motives.

Since all nation-states have laws of one sort or another, it can be assumed that an assortment of countries cooperate in this heavily cloaked dagger-wielding, quite apolitically. The badgeless and uniformless cops are identified as members of an invisible organization called U.N.C.L.E. simply because the producers originally thought the combination of initials "provocative" and "funny," with familial overtones suited to family entertainment. When enough viewers became convinced that U.N.C.L.E. had a connection with Uncle Sam and/or the United Nations, the producers decided they had better invent some words to go with the initials. Months after the show went on the air, the producers agreed, following extensive conferencing, on what U.N.C.L.E. stood for.

The program, while devoted to the thesis that East and West can co-exist and even team up because of a mutual passion of legality, rather perversely implies that the sturdiest Iron Curtain of all is the sartorial. As the capitalist defender of order, Napoleon sports an impeccably elegant Cary Grant wardrobe. As his proletarian counterpart, Illya patrols the globe in plain pullover and no-nonsense Leninist boots.

"The target city for our weekend visitation is carefully selected,"

McCallum explains. "It can be Atlanta or Detroit or Baltimore or Des Moines—wherever

there’s a soft-spot in our ratings profile, an area in which our popularity

could stand a boost. Sometimes Bob Vaughn is dispatched to do the boosting,

sometimes myself. Boosting ensues, I suppose. Whatever gets boosted, it isn’t

my morale."

Understandably. Up until recently a turtleneck was just a sweater with a third sleeve. Today, if it surrounds McCallum’s cat-quick body and is topped by McCallum’s massive-jawed face and trim eaving of yellow hair, it is, to the 10,000 infatuates who write fan letters each week, and to the 20 million less articulate but equally smitten viewers backing them up, the emblem of Muscovite Hip and the signal for crashing police lines.

"Why must they express their adoration for Illya through the most determined efforts to dismember me?" McCallum asks. "Don’t they know I’m an innocent bystander in all this? Whatever this lethal implementation of the warmest amoristic emotions may mean, it’s clear that an astonishing number of Illya addicts would like nothing better than an opportunity to hug me to death. Literally, I’m often moved to point out that it’s a case of mistaken identity, but there’s not time, riots flurry up so fast."

And so lethally. In an auditorium in LaGrange, Ill., rampaging teenagers wearing U.N.C.L.E. T-shirts came close to drawing and quartering their idol before the riot squad could spirit him away . . .("Positively Manichean, they were. The traditional barriers between love and homicide quite gone.") In Baton Rouge, La. a grandmother pursued him with such muscular affection that he had to take refuge in a ladies’ washroom nearby. ("I followed my instructions from the MGM publicity department to the letter. I held doggedly to my charming smile. But I was bleeding profusely. From such multiple embraces, multiple contusions.")

McCallum’s motorcades are now, by order of police chiefs of the cities he visits, forbidden to stop anywhere along the line of drive. He is never within viewing range of any one set of worshipful eyes for more than a few seconds. If the entourage slowed, there would be carnage in the streets, with McCallum as the focal point.

"The sudden mass adulation has overtones of mayhem it would be instructive to explore," McCallum comments. "On these trips I frequently feel like the Winter Palace being stormed. Let me update that image. Like Watts on the longest and hottest day of a very long, hot summer."

This is not all he feels: "I wonder why they bother to come at all. The gregariousness of Americans is surely one of their more ingratiating qualities. But how gregarious can you get when the limousine carrying the object of your sociable instincts whips by at 40 miles an hour with motorcycle cops ahead, alongside, and arear? These good people are partying with a high-speed haze."

Another reason why McCallum is less than overwhelmed by these dramatic proofs of his magnetism:

"One year ago I couldn’t, as you Americans put it, get arrested.

Another year could conceivably come in which I’d have the same difficulty

attracting the attention of the boys in blue. What makes Tuesday’s headlines

may not command one line in Friday’s obituaries.

"I’m pleased the show’s a success, of course, and it’s gratifying to know people are not indifferent to me, but it’s best not to take these dancing manias too seriously. Group dancing is the least substantial sort of social movement you can stir up. It stops the moment the fiddler snaps a string, and stings snap all the time. Similarly, sweaters unravel."

One reason McCallum couldn’t get arrested in his pre-U.N.C.L.E. phase was no doubt his obscurity. Another was that he was busy with other projects.

"My father was lead violinist with the London Philharmonic and my mother was a concert cellist: naturally they thought it would be quite filial if I devoted myself to the oboe. I wanted to oblige them but it was not to be. However much I may have wanted to blow my own horn, the job was not to be done on an oboe. When I was 14 I took a job as electrician’s helper in a Glasgow theater and I haven’t been out of theaters since, except for a stint in the British Army’s West Africa Frontier Force. I was stationed in Ghana. The British Empire will think twice before sending me out again to protect this or that possession."

McCallum came to his avuncular police work for MGM the long way round. Even before his army service he had done child dialect roles on the BBC, studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, worked as property master with the Glyndebourne Opera Company. After Ghana he toured the English provinces with a stock company, playing as many as 52 roles a year, among them Mercury in Giraudoux’s "Amphitryon 38," the Noel Coward part in "Vortex," the assassin in Sartre’s "Crime Passionel." A contract with J. Arthur Rank let him to featured parts in a string of "modest and sometimes not despicable" English movies.

Hollywood made overtures. McCallum’s American movie credits, all of them acquired before his television debut, are extensive: "Billy Budd" ("I had a sweaty time portraying the young ship’s officer who didn’t want to hang Billy; I kept itching to step out and improvise a peroration against capital punishment with copious quotes from Koestler and Camus"), "Freud" ("I was the revelation of the Oedipus complex to Montgomery Clift, with the aid of a tailor’s dummy"), "The Great Escape" ("I played a superbrilliant electronics mind somewhat less than brilliantly"), "The Greatest Story Ever Told" ("I was Judas Iscariot; appropriately, the fee called for in my contract was in the area of 30 pieces of silver").

In short, under Illya’s chin-scraper is a seasoned performer, half of whose 31 years have been spent on and around all possible varieties of stage. If in his gravity-defying enactment Of Muscovite Groove, McCallum’s tongue sometimes seems to be in his cheek, it is no doubt what the role calls for.

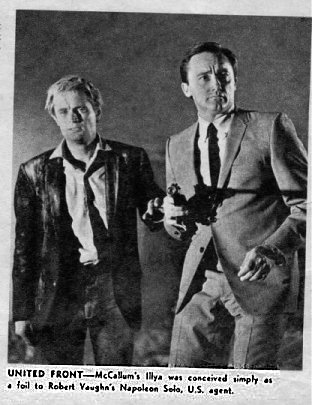

A far cry from Mercury, Noel Coward, Sartre’s killer, tailor’s dummy Oedipus, or Judas, Illya was conceived as little more than a skilled tumbler with a Urals accent, "a servitor forever on the verge of a hiccup," to be the foil to Napoleon Solo as Solo outmaneuvered and outdressed an assortment of global miscreants. What did this young veteran of the theater bring to what was designed as a supporting role to make him blood-brother to the Beatles in teen-agers’ pantheon?

"A climate of negatives, primarily," McCallum guesses. "I’ve

never nailed down anything about this soft-spoken and soft-shoed fellow beyond

his speediness and his molybdenum composure. Illya emerges very much the

enigmatic man because he’s scrupulously undefined.

"A climate of negatives, primarily," McCallum guesses. "I’ve

never nailed down anything about this soft-spoken and soft-shoed fellow beyond

his speediness and his molybdenum composure. Illya emerges very much the

enigmatic man because he’s scrupulously undefined.

"What’s so enthralling about undefinition?

"These days it’s a seller’s market for enigmas. A cryptic character may be attractive to young people precisely because they’re so much at the mercy of their own feelings and can find no area to wear them on but their sleeves: presumably you can’t qualify as a 24-karat enigma unless you’ve made yourself the impresario of your emotions."

Was it McCallum’s plan from the first to give Illya a shimmer of mystery the scripts did not call for?

"No, not at all, in this I imagine I unintentionally channeled something of myself. Look, I wear a wedding ring. I wear it because I’m married and feel thoroughly married and value that feeling. But marital feelings have an underpinning and a validity to the extent that they remain private. I don't like to talk about my family life because families are not, or shouldn’t be, in the public domain along with your dimensions and dietary preferences.

"Well, when I began to play Illya I simply forgot to remove the ring. Pretty soon letters were cascading in by the hundreds asking what sort of woman Illya was married to, how many kids he had, where and why he kept his family locked up offstage, and so on. My reaction was, and happily our producers agreed, why spell out Illya’s background? Why not leave the wedding ring and never say a mumbling word about it. That’s what we’ve done and that’s why Illya’s personal arrangements are as much an abstraction as the Russia he supposedly comes from. This is how bits of my own character have gotten absorbed into Illya by nothing more deliberate than osmosis.

"Maybe this suggests that if you’re good enough at shutting up you may in the end become somewhat glamorous. Though I assure you my untalkativeness comes less from a craving for glamour than from a disinclination to talk. I’m doing my best not to shut up with you. I am aware that it doesn’t make for the richest sort of interview."

Could he expand on the reasons why Illya’s shadowiness of character intrigues so many viewers?

"Maybe because we all live in an atmosphere of intrigue. These days there’s as much scheming in the dry goods wholesalers or the college classroom as in the U.N. To the degree that we’re daily schemers, we strive to be invisible, since you can’t pull any fast ones if you’re very much in sight and can be seen through.

"The defined man becomes fallible and thus loses his omnipotence. The man who is nothing but a black sweater and an unexplained wedding ring and all dry ice in the eyes can presumably perform the wonders he’s called upon to perform in any given 48 minutes of playing time. The kids get the impression that if anything needs solving and Lord knows a good deal in a teen-ager’s life cries out for split-second solutions, why, U.N.C.L.E., if it could spare the time, could certainly drop by and solve it during lunch hour.

"That suggestion of ultimate potency, I dare say, comes in large part from the avoidance of biography, which will cut any superman down to size. I mean, show your typical superman buying braces for the kids’ teeth and trying to unclog the kitchen drain and he looks much less supermanly."

Avoidance of biography, shared biography, is something at which McCallum can claim expertise. He is said to be married to a beautiful English actress named Jill Ireland. (A quick glance at a candid-camera shot shown under the table by an MGM publicist validates the adjective.) He is said to have three sons, Paul, 7, Jason 3, and Valentine, 2. He is said to live with his family in a meandering four-story, 10 room Spanish style home in the Hollywood Hills. He is said to spend all his nonworking hours with his family, concentrating on projects no more derring-do than pruning oleanders.

Wherever the nonworking hours are spent, it is not, this reporter can state

authoritatively, with interviewers. When an interview can’t be avoided, it

takes place during a quick lunch in the MGM commissary with McCallum's family

conspicuous by its absence. When it can be avoided it is, with a skill that

borders on the awesome. McCallum is no less startled by the people who would

leave their homes to ask him questions than by those who surge into the streets

to manhandle any limousine he’s in.

"There are very few people I’d go out of my way to see," he muses. "Not that I’m misanthropic. I’m just taken aback by this apparently wide-spread tendency to get emotional over a highly publicized sweater. I don’t understand the whimsical chemistry in people’s metabolisms which allows for instant mobbism. It’s as if some raging substance gets triggered into their systems causing them to jerk and twitch in a most Pavlovian way: they become frenetic, angular, almost cubist. They’re not potential nut cases, I wouldn’t say that. But neither are they potential friends. You’re not encouraged to socialize with windmills, particularly when they have nails and teeth and a readiness to use them. The more I see of these variegated seethings, the more I stay home."

Did McCallum have any further thoughts as to the program’s phenomenal popularity among young people, specifically? He did. He had six to be exact, six further thoughts, numbered, arranged in logical sequence and, it seemed fair to assume, cross-indexed.

"The Pop culture genealogist of the future may well trace Illya’s family tree to these roots: One, the Liverpool self-expression groups like the Beatles, whose dissonant sounds, are not unrelated to Illya’s dissonant silences. You get the impression that if Illya raised his voice in song he’d make somewhat Khrushchevized Ringo sounds. Two, this is the Year of the European in the States. That provided a ready-made bandwagon on which Illya could hitch a ride to the mass mind.

"Three, Westerners are disturbed by the pall of the unknown that stretches over the Iron Curtain countries. Now here comes the mysterious and ominous Russian and he turns out to look like a customer at some Go-Go stompery, threatening nothing but the eardrums. Four, with the on-the-double dissolution of the family, kids are forced to stand on their own feet early on: they’re becoming loners. And here in Illya is a fellow making a career of loning and seeming to enjoy it, even getting paid well for it.

"Five, with rumors of war all about, with the climate of brinkmanship in which we live, the division between newspaper reality and U.N.C.L.E. fiction tends to wobble; our hijinks look to the young like glimpses of how it really is behind the headlines. Six, teen-agers always need some vogue on which to hang their hats. We don’t deal much in hats, but we’ve made the high-necked sweater very comme il faut."

Did his remarks suggest a personal enthusiasm for the Beatles?

"Very much so. I think they’re a refreshingly healthy spurt of vitality, vivacity, guts. I admire the Beatles for the same reason I’ll always go see Anthony Quinn—nothing wishywashy there—or a film of John Huston’s; it’s not a matter of good or bad but of something positively attempted. Compare the Victorian ballroom with any Go-Go joint and it’s immediately obvious that a set of laws harnessed the Victorian’s that’s been completely slipped out of by the rock’n’rollers. Those delicate folk of times past have become irrelevant in their prudishness and dried-up quality. To be sure there, there was an esthetic element in the Victorian scene that you won’t get a whiff of in the Go-Go. We need that, we’ve lost that. We now have to figure out just how valuable the esthetic is against the vervy. Maybe less so than we thought."

In an article, "Bootleg Romanticism," in a recent issue of her monthly "Objectivist Newsletter," novelist Ayn Rand was complaining that Illya and Napoleon are almost subversive travesties of standard thriller-fiction heroes like James Bond and Mike Hammer. Whereas Bond and Hammer are dead serious against the forces of evil, Illya and Napoleon simper through their enforcing, all but camp, mocking the righteous causes to which they declare nominal allegiance. Did McCallum care to comment? He did:

"We operatives have different styles of course: some work in patent leather and some prefer hobnails. But we are as one in fighting the fight for high ratings."