Look Magazine, 7-27-65

U.N.C.L.E.'s Illya: New Kind of TV Idol

|

|

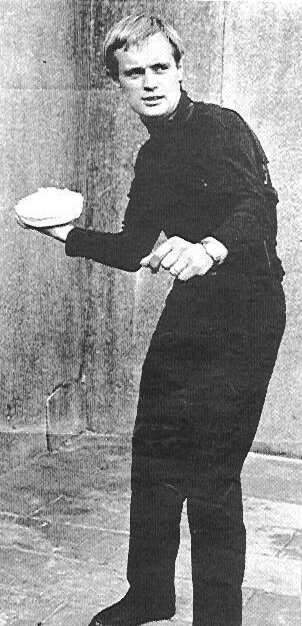

U.N.C.L.E., which also stars Robert Vaughn, is an unpretentious thriller fantasy of evil vs. good. Illya's constant companion in mayhem is this

super pistol. |

PRODUCED BY CHANDLER BROSSARD PHOTOGRAPHED BY DOUGLAS JONES

IN A MEDIUM overburdened with sleepwalkers, maniacal mediocrities, "cutesy" panelists and pea-brained cowboys, the sight of an intelligent, likable, talented performer is almost shocking. Such a one is David McCallum, a cool 32-year-old Scot who plays Illya Kuryakin in NBC's tongue-in-cheek thriller, The Man From U.N.C.L.E. The show's popularity rise has been gradual but steady; in some big cities, it is among the top-five favorites. Yet the truly remarkable thing, considering the usual patterns of mass crushes, is that self-effacing McCallum has emerged, not only as the hottest young television actor around, but a delirium-inspiring, coast-to-coast sex symbol. "Good Lord!" he says. "Think of it. A sexy Scot." Not since the Beatles has anyone been such a threat to wide-spectrum boredom.

McCallum's success in his U.N.C.L.E. role is a triumph of drive over drivel. When the show was launched last fall, his Illya character, as far as the script went, was little

better, in his words, than "a lackey with a suppressed sneeze." Nobody on the show really knew much about Illya. Gradually, dipping into his rather wild imagination (and spurred by a desperate need not to be a lackey), McCallum invented an Illya. "I gave him a background, a private life, a dream life, an interesting accent and two or three basic views of the world," explains McCallum. It worked. The lackey became a star.

|

McCallum expresses his amused-complex view of Illya in the pie-throwing scene above. |

|

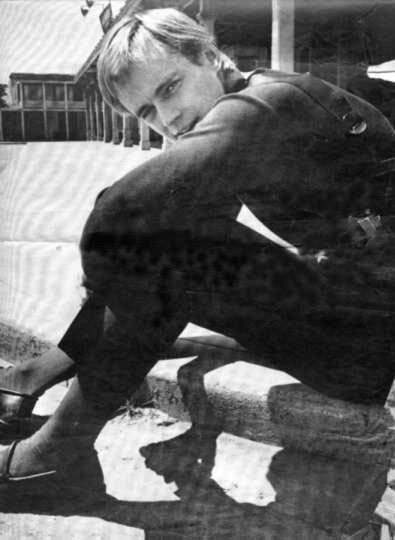

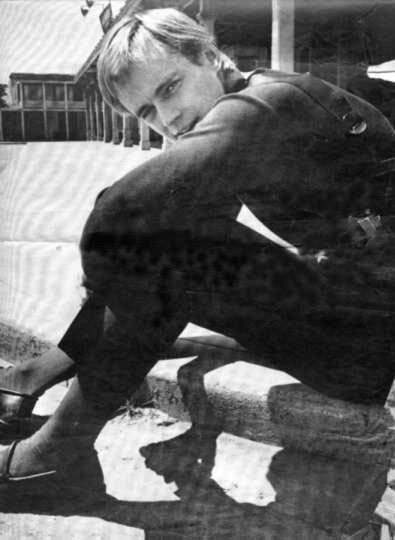

At right, the sexy Scot takes a breather in an MGM "ghost town." |

|

McCallum's exceptional talents have, oddly enough, betrayed him. He is a "private," sensitive, somewhat broody fellow whose inner voice asks only that he be left alone; but his accomplishments have exposed this complex sensibility to the most outlandish mob

scenes, violations of privacy and infantile harassments possible. Except in Hollywood, where the public at large is inured to blinding rights, McCallum cannot buy a hot dog or a dry Manhattan, go for a drive or visit an old school chum without being set upon by howling hordes of adoring fans. "They materialize from nowhere," he says, looking both pleased and pained, "like those strange spirits in children's terror tales. They lurk in the very atmosphere."

Police escorts must be summoned to get him to and from public appearances. "I'm picked up and carried like a football in a mad touchdown run." The fans-most of them teen-age girls-are driven by their hysteria and adoration to grabbing him, picking at him, jumping on him, and even, with clear disregard for life or limb, attacking his car. "I think they want to be run over or have the door slammed on their arms," he moans. "Oh dear, that isn't good. That isn't good at all."

Recently, the peak, or nadir, was reached in privacy violation. McCallum was wakened one morning by strange sounds from outside the back of his house in Hollywood. Shaking the dream fragments out of his hair, he peered through the window and held some of his breath. Down below, going through his trash and garbage baskets like a demented scavenger, was

a perfectly normal-looking middle-aged woman, accompanied by a girl he assumed was her daughter. The woman was handing the girl all kinds of precious Illya trash. McCallum shouted to her to stop it and leave his grounds at once.

"It's perfectly all right, dear," the woman replied, not stopping for a second. "Don't worry about a thing. We all love you."

McCallum could only groan and collapse on his bed, and wonder where it would go next.

Fan mail pours in by the ton-some 10,000 letters per week-and the throbbing, steamy senders range from illiterate subteen-agers to students at Eastern girls' college. "Your show is becoming neater and neater every week. I hear next year it will be in color neatness! ! I can't wate!"

That from a kid. The following from a college: "We are 600 young ladies cut off from civilized society. Our only escape from the cold, cruel world of academics is on Monday [show] night. We watch with some sense of decorum and peace and quiet-although when you kissed Susan Oliver a few weeks ago, one girl knocked over a lamp. My friend said she could probably have learned an extra hundred Chinese characters a month if she hadn't watched U.N.C.L.E.!"

McCallum, who has appeared in a variety of television shows and movies (Freud, The Greatest Story Ever Told, Billy Budd) in addition to years of legit acting in England, is bearing up philosophically under this massive adoration. "Maybe it reflects some deep need in the American psyche to love something or somebody mythical," he ventures. "But then, I shouldn't question my luck, should I? After all, nobody forced me to become an actor. It's my own doing."

Wisely, he feels that his career has just begun. Among his plans: directing "a completely American movie, something peculiar to this country, not fake."

|

|

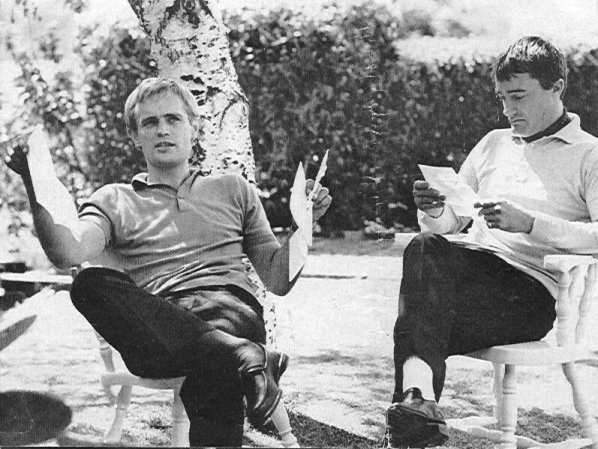

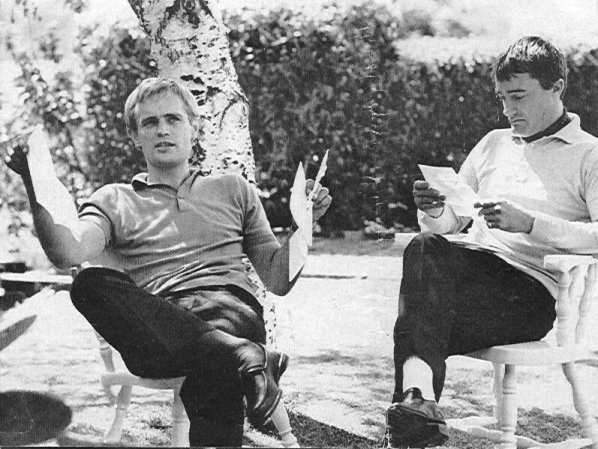

McCallum and co-star Robert Vaughn have a look at some of their fan mail. A good deal of their show is made up as they go along. "It takes all of our ingenuity," McCallum says. "Maybe that's what makes it good."

|