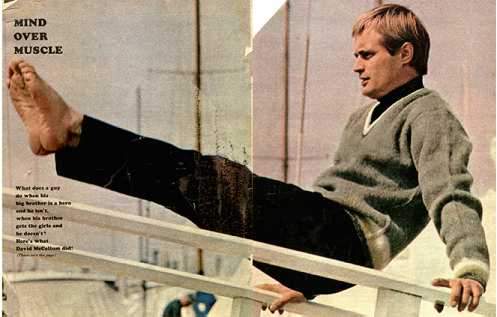

Mind Over Muscle

Mind Over Muscle Mind Over Muscle

Mind Over Muscle

At the ball game - and he's a mad Dodger fan - he goes quietly down the aisle to his seat behind first base, and never moves. That way very

few people even know he's there. They've seen only the back of his head. But let him go up that aisle for a hot dog and he's in the same old

trouble.

Understandable esteem

It took McCallum Minor a hot three hours to catch onto baseball, one wild game two years ago, between the Dodgers and St. Louis, and he's

been a fan ever since. He watched the World Series on his own little TV set between

"U.N.C.L.E." takes. There hasn't been anything like this since rugby. To

David, the mad esteem for athletes is understandable and natural.

What isn't so natural is the same sort of esteem bestowed on actors. Like swimming, acting seems a very personal thing to him, something to

which he was dedicated from the time he made his debut as a very small boy leading

the donkey in a biblical play at church. He joined dramatic activities at school; at thirteen he made his debut on the BBC.

He was already well started on his plan of life, the plan that - if he lived it properly - would enable him to woo a lovely, celebrated young

actress, Jill Ireland, and make her his bride after only three weeks. The plan that

would enable him to become a hero in his own right, with no more need to consider who or what was major or minor. That plan meant simply living his

life his own way, and dedicating himself to it.

Dedication was something that came naturally to McCallum. David's father was lead violinist of the London Philharmonic Orchestra; his

mother, a cellist. He says, "If you meet my father, you know at once the violin is a

part of him. My grandmother was a very devout Presbyterian who wanted my father to play the harp; that's why she named him David. But they lived in

a little Scottish mining town and there wasn't a harp to be found in town. So she got him a violin instead. She made him get up every

single morning at 4:30 and practice - every single day. Saturdays, Sundays, he got up at 4:30 and

practiced. He never rebelled."

And in a way, McCallum Minor was much like his father. Except of course, *he* rebelled. His instrument was the oboe and he played it fairly

well, well enough so his dad wanted him to study at the Conservatory in Paris. He

wanted to study acting.

"My parents were against acting, very wisely and very strongly against it," he says. "My father is a practical Scot. When I'd left home and was

working as a stage manager and making no money, acting in repertory and earning the equivalent of twenty-five dollars a week... it was then

the paternal hand came down. 'You're better than this,' he said, 'if this is as

far as you're going, you'd better give up.' It was not acting per se he disliked or distrusted. It was the lack of funds that usually goes with acting.

"But for some reason I felt very warmly toward acting. I still do. I think your profession, if you didn't enjoy it, would be death. I don't think I'll ever stop enjoying the series."

When the elder McCallum was on a fifty-eight city tour of the East with Mantovani's famed orchestra, father and son met in New York. David was doing a "Hullabaloo" and a "Johnny Carson" show. Mr. McCallum could see that the business he'd originally distrusted "and rightly" has been good to his younger boy.

"I'm lucky," David says. "I think children who are brought up in a home that's secure, as mine certainly was, and who have a normal childhood with normal parents, where everything they need is provided, are off to an excellent start... so long as too much is not provided. Everything I wanted, I had. That was inherent to our childhood, my brother's and mine. But we were expected to get out and earn a living, and this is important too.

No silver platter

No silver platter

"Sometimes people grow up in a home where there is such economic security that there is no incentive to do anything.

"I would hate to have had a father with a big firm like all those old movies Jimmy Stewart and Gary Cooper used to make, where the son was handed the business on a silver platter, when all he wanted to do was put on old clothes and pretend he was an ordinary worker. And then along would come Jean Arthur..."

Jean Arthur comes into any McCallum conversation about films; she is David's all-time favorite actress. "And so along comes Jean Arthur who really shows him how the workers feel, and then she finds out he's the boss and is furious, except of course, he finally saves the day. But I'd have hated not to have had some struggle."

Well, David had a struggle. As a stage manager and in repertory and stock, you work twenty-four hours a day. He still remembers that he spent every cent he earned on food. He had to keep stoking up all day. That was true when he was property master with the Gyndebourne Opera Company. It continued to be true when he came back from his hitch in the army and joined a stock company. He played roles in as many as fifty-two plays a year!

It was at Oxford where he was having a wonderful time doing "all the musty old plays" that he was seen by a film director who was doing his first directing, and a producer who was making his first film. What they saw actually was a still photo of David, and the producer's wife liked his face. He went to work and made eight pictures before coming to Hollywood. Some of them were pretty good character parts: "Robbery Under Arms," during which he met and married the picture's star, Jill Ireland; "Billy Budd"; "Freud"; "The Great Escape." He came to Hollywood to play in "The Greatest Story Ever Told."

But all along the way, he was furthering his goal. He and his wife Jill had agreed they should come to Hollywood, because the chances were greater. They agreed he should try television because it offers such tremendous exposure. Jill, who'd been a successful film and TV star in Britain before her three children, is working in the TV medium now, too. Her most ironic assignment to date, the recent one on "U.N.C.L.E.," coincided, alas, with David's trip to New York for

"Hullabaloo." They wanted to go to New York together, but Jill is, after all, a professional.

"Don't worry," were her parting words. "I'll keep your dressing room warm for you." And when he came back, he found written boldly on the mirror in red lipstick, "Thank you for the use of the hall."

Not the end

As for David's career... "It's very rewarding when you've worked for such a long time and tried to plan things, to see them come out. This is by no means the end, but it's a very interesting step. Neither Jill nor I are willing to let acting be the predominant force in our lives, because pictures, all acting, the whole entertainment business as such, is fast moving and has no great depth. It's a fairly shallow level, not enough to live on."

He's always felt that people learn a lot by being trod upon. "Not very young children, of course, they need protection. But the moment you're able to understand what it's all about, I think you should start learning. If you're trod upon and spring back, you've learned something. If you're trod upon and don't get up, somebody else will step on you and someone else, until you're beaten into the dirt.

"I think a goal is very important. My own feeling is that if one doesn't have a built-in goal, the best thing is to try something, make up a thesis and try it out and be sure it doesn't work before you discard it for another try in another area.

"A blind uncle of mine said something to me when I was very young, I believe I was no more than seven, and this blind uncle said: 'You should think of life as going along a road while far far ahead of you is this tiny light. Keep your head toward it. Just keep going towards it.' He was a very religious man, my Uncle John, and his concept was very close to that of Christian in 'Pilgrim's Progress.' I was deeply impressed. It was such a romantic image as he conveyed it, and it's probably been in my subconscious ever since."

Even when he was acting as referee on the touch line in those long-ago rugby games, David was no second-class citizen, basking in reflected glory. He was McCallum Minor, but his whole life was

preceding along toward that tiny light. On the long road, he has grown, he has matured, he has become a very major McCallum. And to his thinking, and to ours, he's only just begun.